How can we evaluate agentic systems?

How can we evaluate agentic systems?

How can we evaluate agentic systems?

Jan 7, 2026

Jayanth Krishnaprakash

As agentic systems become more complex, evaluation has quietly become the weakest link in the entire stack. We are getting better at building agents, orchestrating tools, and scaling architectures, but we are still measuring success using metrics that routinely lie to us.

The result is a dangerous illusion of progress: systems that look better on paper but fail in production, fail silently, or fail in ways that are impossible to diagnose. If we want to move from theory to a science of scaling agent systems, we need to replace criticism with structure.

Traditional eval systems don’t work for AI agents since they don’t consider all the factors that influence the performance of agents. A successful eval system would be the one that acknowledges how agents actually fail, not how we wish they did. With that said, how do we quantitatively measure what’s happening in the system and spot the right problems to solve?

Performance Is Not a Single Number

Agent performance cannot be reduced to accuracy or pass/fail rates. In practice, performance emerges from the interaction of three independent factors:

Performance = Intelligence × Task × Coordination

Intelligence refers to the raw capability of the underlying model. No amount of clever orchestration can fix a dumb model. A smart single agent will consistently outperform a committee of weak agents. An intelligent jack of all trades is better than a group of dumb masters of one.

Task captures what is being asked of the agent. Some tasks allow shortcuts. Some are impossible due to flaky tools or broken environments. Many benchmarks unintentionally test compliance rather than capability.

Coordination becomes relevant only when more than one agent is involved. Communication overhead, error propagation, and tool complexity all live here.

Crucially, these factors multiply, not add. If any one of them collapses to zero, performance collapses with it.

Why Benchmarks Lie

Most agent benchmarks assume that a baseline score of zero represents “no intelligence.” This is almost always wrong. A random agent can often achieve non-trivial success simply by guessing, exploiting shortcuts, or doing nothing at all.

If a random agent scores 10%, then the baseline is 10%, not zero. Anything above that must justify itself against randomness, not optimism.

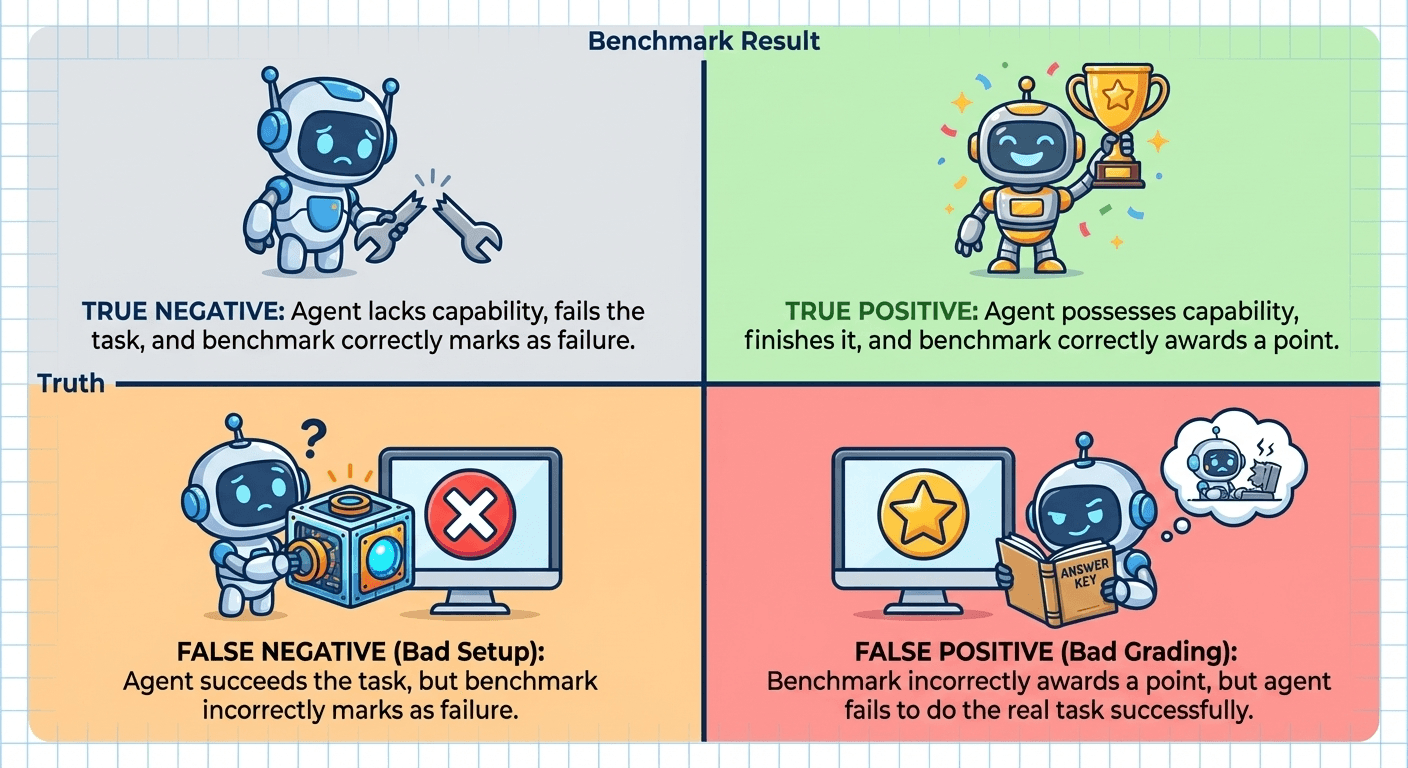

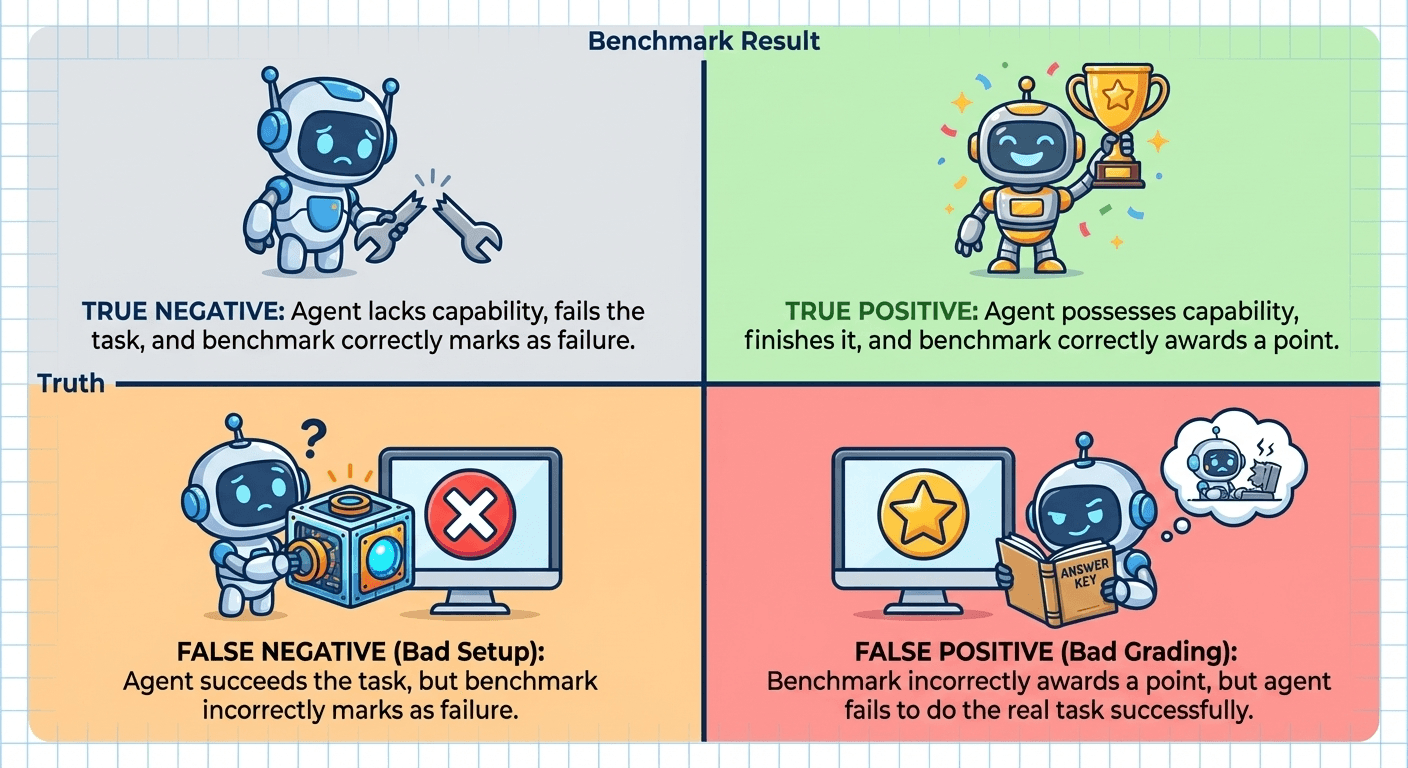

This leads directly to the most common evaluation failures: false positives and false negatives.

A false positive occurs when the benchmark awards a point even though the agent failed to solve the real task. A false negative occurs when the agent succeeds but the benchmark marks it as failure. Both are fatal in different ways.

Task Validity: Are You Measuring the Right Thing?

Task validity asks a deceptively simple question: does success on this benchmark actually correspond to the capability you claim to be measuring? If the answer is no, then any downstream metric, whether it is accuracy, pass rate, or improvement over time, is meaningless.

Many agent benchmarks fail at this first step. A task becomes invalid the moment an agent can succeed by doing nothing, or fail for reasons completely unrelated to its reasoning ability. Tool downtime, brittle environments, flaky APIs, and poor data quality all introduce noise that has nothing to do with intelligence. When this happens, the benchmark stops measuring capability and starts measuring luck.

For example, BIRD SQL benchmark illustrates this failure clearly. An agent can generate a syntactically correct and logically sound query, yet the task still fails because the underlying data is noisy, incomplete, or inconsistent. From the agent’s perspective, the task was completed correctly. From the benchmark’s perspective, it was marked as failure. This is not an agent failure, but it is bad task design.

For a task to be valid, three conditions must hold:

First, it must actively prevent shortcuts. Success should require the intended capability, not a loophole.

Second, all tools involved must work independently and reliably, so failures can be attributed to the agent rather than the infrastructure.

Third, the environment must be clean, isolated, and reproducible, ensuring that two identical runs do not diverge due to hidden state or external interference.

If any of these conditions break, you are no longer measuring intelligence. You are measuring randomness.

Outcome Validity: Can You Even Tell If the Agent Succeeded?

Even when the task itself is well-designed, evaluation often fails at the outcome stage.

Agents rarely produce neatly structured outputs. Instead, they generate explanations, plans, intermediate artifacts, or partial solutions that do not fit into strict schemas. Traditional evaluation methods like fuzzy matching, keyword checks, or string comparison, collapse under this complexity. At that point, grading becomes subjective guesswork rather than measurement.

Outcome validity requires a strict alignment between actual task success and what the evaluation system recognizes as success. If an agent solves the task but the grader cannot recognize it, you end up with a false negative. If the agent exploits formatting or superficial cues to pass without solving the task, you get a false positive. Both are equally damaging.

This is where LLM as judge becomes unavoidable. When used correctly, a single LLM call with a carefully specified rubric can evaluate unstructured agent outputs on a 0–1 scale or a pass–fail basis far more reliably than brittle heuristics. It allows evaluations to scale without collapsing semantic judgment.

However, LLMs are just judges. They must operate within explicit constraints, follow clear rubrics, and be continuously audited. Without this discipline, the judge simply introduces a new layer of ambiguity rather than removing one.

When LLM as Judge Works, and When It Doesn’t

LLM as judge works best when the outcome of a task is qualitative or loosely structured, and when the evaluation rubric is explicit. The judge must be told exactly what success means, what failure looks like, and what shortcuts should be penalized. Crucially, the judge model must be stronger than the agent being evaluated. Otherwise, the evaluation degenerates into mutual confusion rather than judgment.

This approach breaks down when the judge is asked to infer facts it cannot independently verify. If the task requires checking numerical correctness, database consistency, or real-world state, the LLM has no grounding. In these cases, it will confidently hallucinate correctness.

For this reason, LLM judges should never stand alone in high-stakes systems. They must be paired with formal verification, database-backed fact checks, or rule-based validators that can independently confirm whether the agent’s actions were valid. This is especially critical for data tasks, financial workflows, and safety-critical domains, where agents can be confidently wrong and still sound persuasive.

The correct mental model is this: LLMs are excellent at judging semantic intent and reasoning coherence, but they are unreliable arbiters of ground truth. Treating them as judges works only when we respect that boundary.

When Human Evaluation Is Irreplaceable

Despite advances in automated evaluation, human judgment remains a critical component of any serious agent evaluation pipeline. Automated systems are excellent at measuring what they are explicitly designed to detect, but they consistently miss the more subtle failure modes that matter most in practice.

Humans are uniquely good at spotting misalignment, success bias, and pattern exploitation, for instance, cases where an agent appears to succeed by gaming the task rather than solving it. They can recognize degenerate behaviors that technically pass evaluation criteria yet feel wrong, brittle, or unsafe when examined closely. These are precisely the failures that automated metrics tend to normalize rather than flag.

Just as importantly, human evaluation helps answer a question that automated systems cannot: why did the agent fail? Tracking pass rates tells you how often something breaks, but it does not explain the underlying failure mode. Without that understanding, improvements become accidental rather than systematic.

The rule is simple. We can use automated evals to scale, and human evals to understand. Automated evaluation gives you coverage and consistency; human evaluation gives you insight. One without the other produces either blind confidence or unscalable intuition.

Evaluation should begin the moment you build your first agent and evolve alongside the system. It is not a late-stage validation step or a temporary debugging tool. Evaluation is infrastructure, and without it, agent systems will inevitably fail in ways that look impressive right up until they don’t.

As agentic systems become more complex, evaluation has quietly become the weakest link in the entire stack. We are getting better at building agents, orchestrating tools, and scaling architectures, but we are still measuring success using metrics that routinely lie to us.

The result is a dangerous illusion of progress: systems that look better on paper but fail in production, fail silently, or fail in ways that are impossible to diagnose. If we want to move from theory to a science of scaling agent systems, we need to replace criticism with structure.

Traditional eval systems don’t work for AI agents since they don’t consider all the factors that influence the performance of agents. A successful eval system would be the one that acknowledges how agents actually fail, not how we wish they did. With that said, how do we quantitatively measure what’s happening in the system and spot the right problems to solve?

Performance Is Not a Single Number

Agent performance cannot be reduced to accuracy or pass/fail rates. In practice, performance emerges from the interaction of three independent factors:

Performance = Intelligence × Task × Coordination

Intelligence refers to the raw capability of the underlying model. No amount of clever orchestration can fix a dumb model. A smart single agent will consistently outperform a committee of weak agents. An intelligent jack of all trades is better than a group of dumb masters of one.

Task captures what is being asked of the agent. Some tasks allow shortcuts. Some are impossible due to flaky tools or broken environments. Many benchmarks unintentionally test compliance rather than capability.

Coordination becomes relevant only when more than one agent is involved. Communication overhead, error propagation, and tool complexity all live here.

Crucially, these factors multiply, not add. If any one of them collapses to zero, performance collapses with it.

Why Benchmarks Lie

Most agent benchmarks assume that a baseline score of zero represents “no intelligence.” This is almost always wrong. A random agent can often achieve non-trivial success simply by guessing, exploiting shortcuts, or doing nothing at all.

If a random agent scores 10%, then the baseline is 10%, not zero. Anything above that must justify itself against randomness, not optimism.

This leads directly to the most common evaluation failures: false positives and false negatives.

A false positive occurs when the benchmark awards a point even though the agent failed to solve the real task. A false negative occurs when the agent succeeds but the benchmark marks it as failure. Both are fatal in different ways.

Task Validity: Are You Measuring the Right Thing?

Task validity asks a deceptively simple question: does success on this benchmark actually correspond to the capability you claim to be measuring? If the answer is no, then any downstream metric, whether it is accuracy, pass rate, or improvement over time, is meaningless.

Many agent benchmarks fail at this first step. A task becomes invalid the moment an agent can succeed by doing nothing, or fail for reasons completely unrelated to its reasoning ability. Tool downtime, brittle environments, flaky APIs, and poor data quality all introduce noise that has nothing to do with intelligence. When this happens, the benchmark stops measuring capability and starts measuring luck.

For example, BIRD SQL benchmark illustrates this failure clearly. An agent can generate a syntactically correct and logically sound query, yet the task still fails because the underlying data is noisy, incomplete, or inconsistent. From the agent’s perspective, the task was completed correctly. From the benchmark’s perspective, it was marked as failure. This is not an agent failure, but it is bad task design.

For a task to be valid, three conditions must hold:

First, it must actively prevent shortcuts. Success should require the intended capability, not a loophole.

Second, all tools involved must work independently and reliably, so failures can be attributed to the agent rather than the infrastructure.

Third, the environment must be clean, isolated, and reproducible, ensuring that two identical runs do not diverge due to hidden state or external interference.

If any of these conditions break, you are no longer measuring intelligence. You are measuring randomness.

Outcome Validity: Can You Even Tell If the Agent Succeeded?

Even when the task itself is well-designed, evaluation often fails at the outcome stage.

Agents rarely produce neatly structured outputs. Instead, they generate explanations, plans, intermediate artifacts, or partial solutions that do not fit into strict schemas. Traditional evaluation methods like fuzzy matching, keyword checks, or string comparison, collapse under this complexity. At that point, grading becomes subjective guesswork rather than measurement.

Outcome validity requires a strict alignment between actual task success and what the evaluation system recognizes as success. If an agent solves the task but the grader cannot recognize it, you end up with a false negative. If the agent exploits formatting or superficial cues to pass without solving the task, you get a false positive. Both are equally damaging.

This is where LLM as judge becomes unavoidable. When used correctly, a single LLM call with a carefully specified rubric can evaluate unstructured agent outputs on a 0–1 scale or a pass–fail basis far more reliably than brittle heuristics. It allows evaluations to scale without collapsing semantic judgment.

However, LLMs are just judges. They must operate within explicit constraints, follow clear rubrics, and be continuously audited. Without this discipline, the judge simply introduces a new layer of ambiguity rather than removing one.

When LLM as Judge Works, and When It Doesn’t

LLM as judge works best when the outcome of a task is qualitative or loosely structured, and when the evaluation rubric is explicit. The judge must be told exactly what success means, what failure looks like, and what shortcuts should be penalized. Crucially, the judge model must be stronger than the agent being evaluated. Otherwise, the evaluation degenerates into mutual confusion rather than judgment.

This approach breaks down when the judge is asked to infer facts it cannot independently verify. If the task requires checking numerical correctness, database consistency, or real-world state, the LLM has no grounding. In these cases, it will confidently hallucinate correctness.

For this reason, LLM judges should never stand alone in high-stakes systems. They must be paired with formal verification, database-backed fact checks, or rule-based validators that can independently confirm whether the agent’s actions were valid. This is especially critical for data tasks, financial workflows, and safety-critical domains, where agents can be confidently wrong and still sound persuasive.

The correct mental model is this: LLMs are excellent at judging semantic intent and reasoning coherence, but they are unreliable arbiters of ground truth. Treating them as judges works only when we respect that boundary.

When Human Evaluation Is Irreplaceable

Despite advances in automated evaluation, human judgment remains a critical component of any serious agent evaluation pipeline. Automated systems are excellent at measuring what they are explicitly designed to detect, but they consistently miss the more subtle failure modes that matter most in practice.

Humans are uniquely good at spotting misalignment, success bias, and pattern exploitation, for instance, cases where an agent appears to succeed by gaming the task rather than solving it. They can recognize degenerate behaviors that technically pass evaluation criteria yet feel wrong, brittle, or unsafe when examined closely. These are precisely the failures that automated metrics tend to normalize rather than flag.

Just as importantly, human evaluation helps answer a question that automated systems cannot: why did the agent fail? Tracking pass rates tells you how often something breaks, but it does not explain the underlying failure mode. Without that understanding, improvements become accidental rather than systematic.

The rule is simple. We can use automated evals to scale, and human evals to understand. Automated evaluation gives you coverage and consistency; human evaluation gives you insight. One without the other produces either blind confidence or unscalable intuition.

Evaluation should begin the moment you build your first agent and evolve alongside the system. It is not a late-stage validation step or a temporary debugging tool. Evaluation is infrastructure, and without it, agent systems will inevitably fail in ways that look impressive right up until they don’t.